Introduction

Kids Play

**

Toys

Games

**

Senet

**

Dogs and Jackals

**

Mehen

Sports

**

Archery

**

Boating

**

Boxing

**

Bull Fighting

**

Chariot Racing

**

Equestrian Sport

**

Football

**

Handball

**

Hockey

**

Hunting

**

Marathon Running

**

Heb Sed Festival

**

Tennis

The Performing Arts

**

Concerts

**

Dancing

**

Musicians

**

Singing

**

Theater

Other

**

Animal Taming

**

Gardening

Introduction

In Ancient Egypt, the most illustrated activities are the many sports and games in which both royal and non-royal

men, women, youths, and children engaged, whether for training and strengthening their bodies or for pleasure and recreation.

In general, sports were divided into two categories: sports of the entertainment and fitness sort included acrobatics, gymnastics,

high jump, hunting, and swimming; sports of the military training sort included archery, boxing, equestrian activity, marathons,

and wrestling. It is difficult to determine whether or not the depictions of these various sports are pictured in the way

the ancients actually played them, but one thing is certain: whether painted, carved or found in tombs, temples, or pyramids,

these records are rich in artistry and massive in quantity. In terms of the latter, nowhere is this more evident than at Beni

Hassan and in Theban tombs, which depict acrobatics, archery, ball games, boxing, dancing, fencing, gymnastics, high-jump,

hockey, hop and jump, horse-riding, running, swimming, weight-lifting, wrestling, and yoga. From the quantity and care the

artists took in documenting these recreational activities, one understands that the ancients held a high reverence for physical

fitness, placing an invaluable role in sports in order to raise the standard of health and of national productivity, and engaging

in such activities with a fervor that is ritualistic. As an example of this, Egyptian men are illustrated as lean, muscular,

and strong and women are shown to be slender and gracefully feminine.

The area of paramount importance for sports and recreational activities was the River Nile. Sports and recreational activities done here included boating, fishing, hunting,

rowing, and swimming. The desert herself was yet another location of import when it

came to sports and recreation, notably for hunting.

In some way or another, most sports--be they organized, individual, or of the leisurely kind--the ancient

Egyptians established a set of basic rules, which were more pronounced for organized sports. For the more organized sports

competitions, the ancients chose a referee to uphold the rules of a game; required players to wear uniforms; and announced

winners of competitions and awarded them colored collars of ribbons, depending on their placement, similar to different colored

ribbons for multiple-person games. Not only did Egyptians play with their fellow countrymen, but also they played (competed,

rather) with their neighbors, such as the Nubians. Referees from both Egypt and other lands enforced the rules and,

it was typical that, if the foreigner lost the competition and if he was before Pharaoh, he would have to accept his defeat

by kissing the ground before the ruler.

The following examines the many types of recreational activities in which the ancients engaged, as seen from the many depictions

that have survived for more than 3,000 years, and which spread from Egypt to Phoenicia, Carthage, Greece, and Rome.

Back to top

Kids Play: Children's Sports and Games

Unlike that which men and women played, children and adolescence played less organized games, which tested their balance, strength, strategy, dexterity,

and hand-eye coordination. Similar to today, in ancient times boys' games were more fierce and competitive than those that girls played.

however, girl were--and are--known to indulge in a little fighting and hair-pulling when the occasion called for

it.

Most child's play included games that implemented a ball. Rubber neither having been invented yet nor known to the ancients,

leather skin filled with chaff or dried papyrus reeds wound tight together with strings or rags were used as materials for balls.

As with organized games played by adults, children's games had some structure to them in that they too had rules.

On the other hand, different from organized games played by adults, children's games had a very violent approach to refereeing

games: if a player was found cheating, violating the rules, they were punished by receiving kicks and punches, and at

times, by being tied up and flogged. How often this happened is undetermined, lost to history.

The oldest of all children's games were marble games, probably played like the game of Skittles. However, instead of pins,

the ancients used three small marbles and two large marbles--one black, the other white

This marble game, like Skittles, was probably played by setting the five marbles in a semi-circle a distance

away from the players, of which there might have been two or more. The object of such a game would most likely have been to

roll another marble or ball toward the semi-circle of said marbles. Hitting one or more would most likely have

meant that the player who rolled the marble or ball scored a number of points. Again, this is pure speculation.

Other equipment used in children's games were spears or a block of wood. Boys played a gamed called

Shezmu, who was originally a god of the wine and unguent oil-press as well as an underworld deity. This was a spear-throwing

game of sorts, where the player most likely competed with others. The concept of this game was similar to that of darts,

where each player had to through his spear at a target, which was drawn on the ground. A variation of this appears to be an

archery competition, where several players use bows and arrows to aim, shoot, and hit a target made of animal skin. Both the

point system and the general set of rules for either variation of archery game are yet unknown to us. The child's game

for which one used a block of wood was a Middle Kingdom game called

Tipcat.

This was most likely a solitary game. To enjoy this game, one held a stick in one hand and hit with the other the end

of the stick closest to the ground on one of the tapered ends of a block of wood. Hitting the piece of wood would cause it

to spring up into the air and, while it was still airborne, one hit knocked it away, much like one would a baseball with a

baseball bat.

One popular game played among boys was a sort of wrestling match, where two boys faced each other. Behind

these two boys, other competitors formed a row, each holding on to the boy in front of him, forming a human chain. The leaders of each chain began wrestling,

while those behind each player cheered them on. Perhaps these cheering boys would be next in line to wrestle the winner or

perhaps it was a game played in the style of Around the World, the last boy to beat all was the winner. This is pure speculation,

of course. This was not the only form of wrestling game done in Ancient Egypt: boys and girls alike sat piggyback on each

others' backs and tested their ability to stay on. The object of this game was to avoid being thrown off, almost

like a human bull ride.

Yet another game that required physical contact between two or more players was a game that resembles the western version of Heads

Up Seven Up. The western version requires everyone but a few people to conceal their eyes by putting their heads down on their arms and then sticking their thumbs up

before the heads. The seven who are standing must go around the room or designated area and stick any person's thumb

into this person's fist. When these seven have completed their task, they all say "heads up seven up" whereupon

everyone who concealed their eyes must open them. Those whose thumbs have been pressed down must guess who did this from the

seven who are standing up. Depending on the way one plays it, if the person guesses correctly, then the person who pushed

in the thumb takes the place of the person whose thumb he pushed in or the person who guessed correctly joins the seven. The

way the Ancient Egyptians played their version of this game was to have one person crouch down, with knees and arms folded

under his/her torso. Two or more persons would then surround the crouched person and start pounding their fists on the

crouched person's back. The crouched person, not being able to see who is hitting him, would have to guess who hit him each time.

Another game played among children in ancient times as well as in present day in Lower Egypt was somewhat like Red Rover. In ancient

times, this game was called The Kid is Made to Fall. The set up of this game was thus: two crouched players on one end of a

designated area held on to each others' arms, locking them tight to make a human fence, an obstacle over which a line

of players on the opposite end of the area jumped. All jumpers announced when they were going to jump, after which the two players on

the opposite end then raised or lowered their arms in order to prevent the jumper from succeeding in hurtling over them.

The following is perhaps the same sport, only called by a different name: this game is still played in Egypt and is called Goose Steps, where players jumped over

the obstacle that two others created with their arms and legs. After all the jumpers went through their turns, they would

go again, where, on the other end they would meet a high obstacle, which would consist of leg stacked on leg stacked on hand

stacked on hand, getting higher and higher as the high jump competition grew harder and harder. Evidence of such a game appears

in the tomb of Mereruke in Saqqara, which dates to Dynasty VI, circa 2250 B.C.E.

Other Ancient Egyptian children's games that are still seen in modern day are tug of hoops and tug of war. The former was a game that

required good hand-eye coordination. Two players compete against the other, trying to keep his hoop rolling as he ran,

using a hooked staff that was also used to off-set the opponent (a rather nasty tactic, but part of the game). The latter

game, tug of war, required a much larger group of people; no less than two people could play this game. Tug of War was like

the modern game of the same name that usually employs a rope that is pulled from both ends by a group of people vying for victory, hoping to pull

the opposite team over the center and onto the ground. In Ancient Egypt, two opposing teams would execute this game in much

the same fashion, yet without the use of a rope. Instead, the two leading people, one from each group of conteners, stood face-to-face,

grasped each others' arms while each team's participants (situated behind the two leaders) grabbed the waist of the person in front of them, planted

the soles of their feet to the other's foot for support, and then started to pull. This game no doubt measured a group's

strength and equilibrium.

The last of children's sports is that of swimming. With the accessability of the River Nile, it is no wonder there has

been found evidence of leisurely swimming and competitions in ancient times (mostly of different swim strokes, found in the tombs of those

buried at Beni Hasan).

Toys

Toys were popular items among Egyptian children during all dynasties, starting as early as the Pre-dynastic Period. The oldest toys

ever found, which date from the Pre-dynastic Period, were small toy boats made from wood. Certain toys were made to represent

both various animals and people and where made from baked clay, bone, ceramics, ivory, stone, or wood. Royal children had

access to toys made from any material, whereas children of the lower classes had access to only clay, which was commonly

formed into dollies. The loveliest of toys found were dolls of Nubians or dolls with jointed limbs (some of these dolls

date to Dynasty XI and some were made in the form of pincushion dolls with long hair or, in some cases found without hair

either by accident or on purpose, as would be the case by taking scissors to a Barbie's hair); pull-string dancing dolls

(evidence of such having been found at el Lisht, where three of such dolls were set in an ivory stand and could be made to spin when

one pulled strings attached to them; another of the same concept found elsewhere represented a slave crushing corn); toy animals such as

horses and crocodile, whose mechanical mouth would open and shut when pulled; spinning tops; and jumping jacks. Some such

wooden toys were in the shape of horses on wheels and, as mentioned before, in the shape of boats.

Back to top

Games

Senet

GENERAL INFORMATION:

Both royal and nono-royal Ancient Egyptians adored board games very much. One of the most popular of such

is Senet. It was an ancient game with many meanings: that of distraction and that of a symbolic, ritualistic meaning. Concerning

the former significance, some illustrations show two people playing the game; concerning the latter, other representations show

one person playing alone with an invisible opponent, as shown in the picture of Nefertiti, below:

The Ancient Egyptians played this game from as early as the Pre-Dynastic period just until the first few centuries after Christ.

Although it is not exactly clear how one played this game, scholars have formulated a set of rules based on what Egyptologists

and archeologists learned from tomb paintings, illustrating rulers playing this game, as well as from texts written on papyrus.

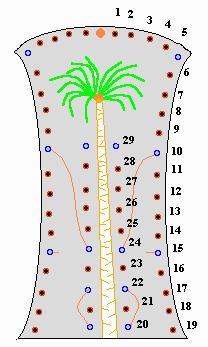

The layout of the board looks like the following [minus the numbers--they are there only to show the direction that the player(s) follow]:

THE BOARD:

This game was also known as the Game of Thirty Squares, in that, on the top of the board there are 30 squares--24 of which are

left blank, while 5 have hieroglyphic pictures on them. The hieroglyphic symbols on each of the last 4 squares are as follows:

a row of three long-necked instruments, representing

nfr, meaning beautiful or

good in Ancient Egyptian; three rows of horizontal and zigzagged lines, representing water (landing on this square might have been a good

or a bad thing: water could mean purification or it could me chaos); a line of three ibis; images of Nephthys and Isis, facing each

other, which possibly meant that if one landed on this square, one was protected by both goddesses; and the last square depicts

a figure of what looks like Ra in falcon form, complete with solar disk headdress. There is also another square (#15) that has written on it the

ankh symbol, which probably

marked the starting point of the game or another safe space. The direction in which each play was to move might have been in the shape of a backwards

"S".

PLAYER PIECES:

The pieces one used to distinguish players were any of the following: pawns, knucklebones or sticks. The number of player pieces

varied, depending on at which tomb painting one looks. Some illustrations show the players using five pieces, some using seven,

while others show them using as many as ten. The discarded game pieces were stored in a drawer that opened from the base of

the Senet board.

RULES OF THE GAME:

Below are links to various rules of the game. Tim Kendall's rules (from the 1970s) seem to be the most sound

and acceptable in that they are based on archeological and textual data (though, this is just my opinion). Another person to create rules to the game of Senet

was RC Bell. His rules are commonly cited and are based on the rules of Tabula, a Roman version of backgammon.

However, since no one knows exactly how Senet was played, it would be erroneous to think of these rules as similar to those

of backgammon.

Tim Kendall's Rules

John Tait's Rules

RC Bell's Rules

Gustave Jequier's Rules

Back to top

Dogs and Jackals

Yet another Ancient Egyptian board game was Dogs (or Hounds) and Jackals. The Ancient Egyptians called this game of Fifty-Eight

Points because there were 58 holed poked into the board's surface. Also on the face of the board was an image of a palm tree.

Because this game was more complex than Senet, adults played, rather than children.

Typically, the game board rests atop a piece of furniture that had carved legs resembling those of an animal. A Dogs and Jackals board

found in the tomb of Reny-Seneb was fashioned of ebony and ivory and dates ca. 1800 B.C.E. or Dynasty XII. Within the drawer

at the base of the rectangular board were found 10 pawns: 5 with the heads of dogs and 5 with the heads of jackals. These

player pieces (rather, sticks) were typically made of ebony. Since there are only two animals represented fro each set of

player pieces, the game allows only two players to play the ancient game. For these pawns there are 58 holes poked into the

surface of the board in which to stick them (29 holes on the dog side; 29 holes on the jackal side). Some of these holes were

inlaid with ivory, probably giving them a more important role in the game. Other holes on the board were left unfilled and

were probably meant to be a means of a shortcut for any of the players, according to some sources.

R.C. Bell's Rules to the Game

PLAYERS:

The game is designated to two players: one player represents the 5 dog-headed sticks and the second player represents the 5 jackal-headed

sticks. The goal is to reach the five holes labeled 25, 26, 27, 28, and 29 on your side of the board to win the game.

MOVING AROUND THE BOARD:

Using three coins or spare change or whatever you have, the rules for moving are as follows:

*one head facing up = move one pace

*two heads facing up = move two paces

*three heads facing up = move three paces

******one cannot move four paces in this game, apparently******

*three Tails facing up = move five paces and you receive another turn

PLAY THE GAME:

1. Both players agree on a wager (say if Sithathoriunet wins, Sathathor must give her opponent her set of diaphanous gowns; if Sathathor wins,

Sithathoriunet must give Sathathor her cosmetic jars). Remember, gambling is frowned upon in the occidental culture, so many

of you should not consider this rule, sorry folks!

2. The right side of the board belongs to the dogs and the left to the jackals.

3. The brown circle above the palm tree is the starting point. Each player is to start off with only one pawn. The direction for

each player to move his or her pawns is marked on the outline of the board, and then continues from the base of the tree trunk

to the top of the tree trunk. Each player's goal is to reach the top of the tree trunk first (holes 25 through 29).

4. Exact throws are required to reach the final positions (holes 25 through 29). The order in which it is done has no importance. In

other words, one does not have to fill each hole in order, starting with 25, then 26 and so on. One could fill hole 29 first,

then hole 25, 27, 29, then 28 or any other order.

5. The two players throw the three coins in turn. A five is required to introduce a new pawn on the starting point (the circle above

the palm tree). Then the coins are thrown again to move the pawn(s).

6. The first pawn to reach a hole with a horizontal mark (hole 15 on both sides) wins the bet (whatever Sithathoriunet and Sathathor

bet each other).

7. Only one pawn may be put on a hole (obviously, the holes are not big enough for more than one, plus this is not

Candyland we are playing here!)

8. If a pawn reaches a hole linked to another hole by a path (holes 10 through 24; 20 through 22, on both sides), it follows the

line, which acts like a ladder to victory (sounds like shoots and ladders, doesn't it?). Let's say one lands on hole 12, then

that player gets to move his or her piece to hole 15.

9. A player may move his pawn when he or she can do so. If one can move no pawns, his or her opponent is allowed to add the unlucky

person's throw to his or her own throw and this unlucky person looses his or her turn. Say Sathathor rolls a three, but is unable

to move because one of her pawns is in the way, that means that Sithathoriunet get to move three paces and Sathathor looses

her turn.

10. The first player having put his or her five pawns in the five holes, numbered 25, 26, 27, 28, and 29, wins the game! This person

may or may not have won the bet, however (just like a candidate for president may have received the popular vote, but did

not become president because another candidate received more electoral votes).

Back to top

Mehen

Back to top

Mehen

This game, also known as the Game of Snake, was another game from Ancient Egypt, was played by everyone, and held religious

significance. The latter statement is evident because it is mentioned in the Coffin and Pyramid Texts. In Ancient Egyptian

history, Mehen was the serpent god who protected Ra during his nighttime voyage through the Underworld. On a more interesting

note, the game and the god seem to have been deliberately synchronized. It is relatively impossible to decipher which one

influenced the other: if Mehen (the deity) inspired the game or if Mehen (the game) inspired the creation of the deity.

The board was composed of squares (or rectangles, depending on your perspective) that coiled up into a ball, which resembled a

coiled serpent. From the known Mehen board games found (about 14), the number of squares varies. However, one thing remains

the same: the squares lack distinguishing marks or images, unlike the game of Senet.

Just as the rules to the game of Senet are unknown, so are those of Mehen and for the same reason: there are no surviving documents

that can tell us what they were. From what has been found in paintings in tombs and from the game itself, one can guess the

function of the game: to win, one must be the first player to reach the center of the board.

Furthermore, one can guess that the game was played with six (or two, according to some Egyptologists) marbles or stones that at most six

(or two) players moved all the way around the board towards the center, which represents the serpent's eye. These game pieces

(six pieces to a person, thus 36 in all...or 12 in all, if there are only two players) were in the form of dangerous and predatory

animals, which included lions/lionesses (the more prominently represented pieces), dogs, or hippos. If, in fact, Mehen permitted

up to six players, then, unlike Dogs and Jackals and Senet, this game was the only known multi-player Ancient Egyptian board

game (remember: for both Dogs and Jackals and Senet, up to two players are alotted).

The first findings of the game of snake date to around 3,000 B.C.E. (or earlier) until about 2,300 B.C.E.. From 2,300 B.C.E. until

700 B.C.E., representations of this game seem to disappear, but reappear after 700 B.C.E. The best representations materialize during

the Old Kingdom and the best illustration of this game is found in the tomb of Hesy-Ra.

A game that seems to resemble the game of snake is the Hyena Game. One reports that during the 1920s, Baggara Arabs of the Sudan

played this game. The board of said game is similar in design to the game of snake: it was of a spiral pattern and one used stick-dice (of the Ancient Egyptian kind) to play

the game and had two player pieces, one of which represented a predatory animal. Again, according to some, the latter characteristic

would not fit the game of Mehen because Mehen permitted six people to play. However, if you are one of those people who believe

that the game allowed only two people to play, then the latter characteristic is valid. Personally, I believe that six people

could play the game at a time, just by looking at the number of spaces on the board. Otherwise, if only two were permitted

to play at a time, then Mehen would be a rather long game to play. Then again, the Ancient Egyptians did not have television

or shopping centers with which to occupy them, so this game could have possibly been meant for only two players.

Consider this: Monopoly is a long game as well, even when there are more than two players playing!

Would you like to try your hand at Mehen?

Click here to be directed to a brilliant website that offers rules to the game and allows you to download the game onto your computer

(the file size is about 1 MB). If you would like to know the rules of the game,

click here. You will be directed to a help file that is from the same website. Here, you will find a list of other games. Look for the

sign that I have placed at the bottom and you will be on your way to playing the most "forbidden" games of ancient times.

Back to top

Sports

Archery

Back to top

Sports

Archery

To start of, let us examine the composition of the bow and arrow of Pre- and Dynastic Egyptian era. Being a weapon of paramount importance, the bow and arrow was a means of recreational sport. Beginning its usage during

the Pre-dynastic Period, some of the first Egyptian bows ever to be created were made by joining

the butt-ends of two antelope horns to a piece of wood (scholars refer to these bows as "horn bows" and both peasants and royals used these bows frequently).

At the start of the Old Kingdom, bows no longer had a double curve that "horn bows" made,

but were of a single curve, looking more like a modern bow. In addition, horns and a piece of wood were no longer used as

construction material; rather, artisans used wood strung with sinews or plant fiber strings to make them. This type of bow was called a "self bow"

or a "simple bow." The length of a "simple bow" was between one and two meters. Its shape was broad at its center, narrowing towards either end.

Simple bows that were closer to two meters in length could be strengthened at various points on the wooden rod by binding on it a cord. Compared

to the Pre-Dynastic "horn bow," the "simple bow" was far harder to use.

Enter the composite bow, which was an adoption during the New Kingdom, sometime during the Second Intermediate Period, and was of

Asiatic Hyksos design. Different from the preceding two bows just described, at this time, bows were imported from the Middle East rather than made within Egypt. Such bows could

be as long as 1.45 meters. The central part of the composite bow was most likely made of the wood from the acacia tree and

was brought together with fish glue on two wood slats. The outer part of the bow was covered with sinew and the inner part

was covered with antelope horn plates. The string that the archer drew back to make fly his arrow was made of four intertwined

animal intestines. Evidence of composite bows has come from the tombs of Amenhotep II and Tutankhamun.

From these bows, one can see how elaborately decorated some could be, bedecked with leather or even gold, inscribed with the

greatness and skill of the owner. In addition to bows and arrows, archaeologists have discovered archer's rings, which archers put around their thumbs to shoot arrows from his bow. Here, one can see how the Ancient Egyptians

pulled the strings--with their thumbs, rather than with three fingers, as is done in modern times. Even though this sort

of bow came into use and was more modern than either the horn or simple bow, the Egyptians did not abandon the latter two. For one thing,

composite bows were much more difficult and expensive to produce than horn and simple bows because the archer was able to

draw the bow at a greater length than he could with a horn or simple bow, whose maximum draw length never exceeded the length

of the archer's arm. In other words, composite bows were more flexible and could withstand the tension of drawing the

string back than could the earlier bows, making them more conevient and more expensive. What is more, the expense of the composite bow depended on the amount of care required

to keep it in perfect condition: being vulnerable to moisture, one needed to cover it and, when not in use, the archer would

have to unstring his bow, then restring it when he used it again--sometimes two people were required to carry out this

process. With these requirements it is evident that peasant archers or hunters with bow and arrow could afford only the horn

or simple bow. This does not mean that the king snubbed his nose up at the thought of using one, no. Because of its simplicity,

pharaohs like Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep II were not beyond using such objects for archery practice, hunting or combat. However,

chariot drivers employed often the composite bow as a weapon during battle, so as to better penetrate the enemies armor.

Arrows used with most styles of bow were made of reed and were fletched with feathers--usually three. Artisans fashioned arrow points

from flint, hardwood, or bronze (bronze replaced flint and hardwood in the second millennium). Ancient arrows could

measure up to 50 cm in length. The sharpness of the point depended on its use: sharper points where made for archery, for

battle, and for large-game hunting, whereas more blunt heads were for small-game hunting.

Archery was both a means of battle and of sport. The following information chronicles its sportive employment. During ancient times, archery--more

precisely, target archery--was a sport played in public and graced the walls of tombs. Skill was not the only element measured in archery competitions but also, the princes' or princesses' ability

to use their strength to draw an arrow. As has been examined already, some bows were harder to draw than others, so it would have been impressive to witness an archer being skilled at the bow that

was the most difficult to handle. A record of an ancient archery competition records that Amenhotep II pierced a thick brass

target with four arrows and had offered a prize to anyone who could equate the feat.

Evidence of this sport can be found at the Luxor Museum: it is a depiction of Amenophis III of Dynasty XVIII and dates around 1,420 B.C.E. Another representation of the sport can be found

at the temple at Karnak. Here, there is a depiction of Taharak of Dynasty XXV, which dates to around 700 B.C.E.

Back to top

Boating, Rowing

One way the Egyptians tested strength was by rowing. Races during ancient

times are similar to those of modern times: a team of men would move their oars at the same time to a systematic and high-pitched

call from the leader, whose place was at the rudder, where he held that boat's appendage and steered the vehicle.

Other than for sport, boating/rowing had another, more religious significance: mostly used for hunting and catching birds and fish, a man

and possibly his wife and children would set out on their merry way down the marshes of the Nile, either collecting lotus flowers

or catching birds in nets or using whatever equipment the man employed. Collecting lotus flowers symbolized new life or rejuvenation and

catching birds symbolized the successful taming of chaos. Such scenes with this religious significance can be found in the

tomb of Queen Meresankh III, possible granddaughter of Khufu and wife to Khafre (her burial place resides on the eastern side of Khufu's

pyramid, in the Eastern Cemetery). Depicted on one relief, she and her mother, Hetepheres II in a boat with two children. The former two and one of the children

are pulling lotus flowers while the other child steers the boat. Other religious significance attached to boats can be seen

near this site, at the Pyramid of Khufu, where several boat-shaped pits and pits made to bury boats can be found. The former pits

were more for religious purposes, perhaps intended to come to life for the ruler in the afterlife to bring him north to the

stars, rise in the east as the setting sun with Ra, or to transport the ruler's

ka through the underworld. The latter

pits, which were actually occupied with disassemble boats, were most likely used as elements in the funerary procession and

might have been used in real life. One of the many disassembled boats found near Khufu's pyramid is comprised of 1,224

pieces, made of cedar wood to look like a papyrus reed boat, originally held together with ropes and pegs but not nails, and

measures 142 ft long and 19 ft wide. The tops of its prow and stern are in the form of papyrus buds. Model boats

were other evidence of the importance of the sport in ancient times. Not only do they reside in royal burial places, but

also in non-royal burial places. This illustrates the lack of social limitation that this sport had in ancient times: it was a

sport and recreational activity that could be enjoyed by both Pharaoh and his subjects.

Back to top

Boxing, Weightlifting, Wrestling

Wrestling was a sport mainly for boys and men. Animals partook also in this sport: there is a representation of a cat boxing a mouse at the Carlberg

Museum. Its date of origin is unknown and it is more than likely a symbolic illustration, rather than an actual boxing match set up

between the two. Inside the bellies of pyramids, we may view possibly the first recordings of this sport, some 3,000 years old, from

the Old Kingdom--and through the New Kingdom, where depictions are located in tombs

and mortuary temples. One can find such a recording, dating to 2,300 B.C.E., inside the tomb of Ptah-hotep, Dynasty V pyramid

builder and vizier. Its location is at Saqqara> and illustrates a group of six young men boxing

and wrestling each other. In addition, at Beni-Hassan there are hundreds of depictions of wrestling group scenes, around 200 to

be exact. These depictions show wrestlers donning loin-cloths and practicing various wrestling positions, holds, and moves

as a means of military training. Such reliefs illustrate both dilettantes and professionals alike executing various moves

and contorting their bodies in an assortment of positions. Within Beni Hassan are prime examples: the tombs of Paket and Khiti

of Dynasty XI, which date to 2,000 B.C.E. Perhaps weightlifting activities were also meant for Egyptian military training, but without sufficient

evidence this is just speculation. However, one can get a sense of how the Egyptians went about this activity from a depiction of weightlifting found in the tomb of Paket

The weights were in the form of heavy sacks of sand and had to be picked up off the ground and held up in the air above the weightlifter's head for an allotted

time. No doubt this measured the sportsman's strength (and it is similar to modern weightlifting).

During the Middle Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII to be exact, and at the tomb of Kheroef at Luxor, there is yet another depiction of wrestling. This dates to about 1,500 B.C.E.

During the New Kingdom, there have been at least five instances where Ancient Egyptians wrestled

against their southern neighbors,the ancient Nubians. It was at the height of Egyptian control over and imperialization of

Nubia that these scenes are most prominent. However, let us not assume that Nubians appeared inferior to the Egyptians. It is from a tomb painting, dating to around 1,410

B.C.E., in the tomb of Tyanen, an officer, that proves otherwise and is the first of five Nubian wrestling scenes mentioned herein. This wrestling

scene represents a wrestling competition as a means of military training for Nubians, whom the Egyptians recruited often in

their battles, even making them their archers (this possibly meant that Egyptians held Nubian wrestlers in high esteem, at least

with regard to warfare). In addition, this depiction illustrates five Nubians marching together. The first four Nubians brandish

sticks, which were sometimes used in dueling tournaments, and the final man in the procession carries a platform on which

a husky wrestler--most likely a Nubian--and a leaner Egyptian wrestle. The appearance of men welding sticks is most

likely a common addition to wrestling during ancient times. Stick-fighting and wrestling appear together, perhaps indicating

that those who wrestled also stick-fought.

On the other hand, wrestling matches might have been a means of illustrating the Egyptians superiority over Nubians, representing Egypt's suzerainty and prowess

over Nubia--an ethnocentric, boastful, fancifully imaginative, and derogatory illustration of their power over their southern

neighbors. One sees an example of this caliber on a relief (the second of five examples), found in the tomb of Meryre at Akhetaten, dating to around 1,355 B.C.E.

Meryre was the palace steward Nefertiti. On the relief, there

is a depiction of a sequence of four scenes, which were carried out as a "tribute match" in front of Akhenaten,

foreign ambassadors, nobles and soldiers. The first scene depicts the Egyptian wrestler in military garb; the second scene

depicts the Nubian in a head-lock; in the third, the Egyptian reaches through the Nubian's legs and pulls his head down;

and the final scene shows a victorious Egyptian, raising his hands in triumph, and the defeated Nubian, over which the Egyptian

stands.

The third evidence of Nubians depicted in wrestling scenes appears also at Akhetaten and dates just five years after the depiction

in the tomb of Meryre. This shows not a tournament for royal affairs, but that of a general match between two Nubians, at

which a woman and a dog gaze. In the same area, we see also Nubians welding sticks, evidence that wrestling and stick-fighting

could be seen used together. The location the sandstone carving shows is the countryside, an informal setting compared to

the king's court.

The fourth and fifth evidence of Nubian wrestling in Egyptian art can be seen at the temple of Ramesses III (pharaoh during Dynasty XX) at Medinet Habu, an arm's

length away from the Ramesseum (the mortuary temple of Ramesses II). This artifact, which dates to around 1,000 B.C.E., was meant to be a prototype made for the latter

location, for Ramesses II. Both the prototype and the one at the Ramesseum similarly depict a Nubian and an Egyptian engaged

in a wrestling match, with Ramesses III's appearing below the Window of Royal Appearance--a window-like structure through

which he appeared in order to collect spoils of war and tribute in his honor. Nevertheless, from both the prototype and from

the Ramesseum depictions, it is evident that, at these wrestling matches, Pharaoh and his court appear as well as a Nubian, possibly

an emissary, bedecked with a plume and an earring. A particularly enthusiastic tournament, it was most likely organized to illustrate

Egyptian power over Nubia. It is also from this depiction that we see stick-fighting and wrestling happening together; a rowdy crowd calling out praises to the

Egyptian, comparing him to Montu and assuring the wrestler that Amun is watching over him; and a vision that negates the fancifulness

of the match: a referee (or a facsimile thereof), whose presences possibly denotes that all abide by an established set of rules and that the

Egyptian and the Nubian have a fair chance at winning the match.

Similar to the relief in the tomb or Meryre, the depictions of a wrestling Egyptian and a Nubian opponent at Medinat Habu are shown

in a sequence of scenes, of which there are three. In the first scene, the Egyptian has the Nubian in a choke-hold, as the

referee reinforces the rules to ensure fair play before the king. The second scene shows the Egyptian forcing his defenseless

opponent to the ground, taunting him all the while--a similar scene is shown on the depiction at the Ramesseum. The way

in which the Egyptian weakens his opponent appears to be thus: he forces the Nubian's left arm into submission and holds him

tightly, leaving the Nubian's legs to crumple beneath him. According to one source, this move would most likely not drive an opponent's

face to the ground as it does the Nubian in this depiction. It might have been the ignorance of the artist that this move

was not properly documented. Rather than follow this sequence of moves to defeat the Nubian, and in true Egyptian technique, the

Egyptian would have employed the following moves: twisting the left arm, forcing the opponent's thumb down, causing

the bent arm to straighten all the while localizing all the pressure on the back of the Nubian's arm. This maneuver

would more than likely have hunched the Nubian's shoulder than the maneuver depicted, but hunch his shoulder the depiction

undeniably shows. And finally, the last scene shows the triumphant Egyptian in a victorious pose similar to the one depicted on

the relief at the tomb of Meryre. Unlike the relief at Meryre, however, the one at Medinat Habu depicts the winner chanting

a victory hymn as the defeated Nubian genuflects to kiss the ground before Pharaoh.

Back to top

Bull Fighting

Being an agricultural civilization, cattle-breeding was eminent in Egypt's development. Depictions of cattle and other breeds of oxen

seem to grace nearly every tomb, whether in a sacred setting, which includes the celestial cow or Hathor, or in the

every day setting, which includes herding, branding, grazing, and fighting. What is perhaps most unusual about

the Egyptians is their association of the bull as a strong, resistless creature; where they compared several of their gods

to the "strong bull," other civilizations compared theirs to the mighty lion. Granted, the ancients revered the

lion just as much as the cow, either was equally strong in their eyes. In fact, the king was often represented with the body of a lion

and his ownw head superimposed on the body.

Now to the matter at hand: bull-fighting was a sport that the Egyptians held in an arena usually during an event known as the gymnastic

games and the bull-contenders, much like in horseracing, had epithets such as "the favorite" or "broad striker."

To entice the bulls into fighting, two men acting as umpires to their own bull would use short sticks. When a clear winner

was observed, this bull would then compete against another with even longer horns and swaddled with a festive cloth. A representation

of this sort can be seen at Beni Hassan and dates to the Middle Kingdom. Other representations of bullfights

can also be seen at a funerary temple in Kerma, just recently discovered. Along with bullfights, these scenes also depicted

fishing, crocodile, and rows of giraffes and hippopotami, the latter two being depicted rarely during ancient times. Such

scenes seen at Kerma are also seen in the Aswan tomb of Sarenpet, a mayor of Khnum, and overseer of the priests of the local temples under the reign of Senusret I during Dynasty

XII.

Back to top

Chariot Racing

Chariot racing was another sport of the public kind. There are no depictions anywhere to suggest the manner the ancients organized

this sport, but we do know that aristocrats who were charioteers enjoyed engaging in this activity, mainly for the glamour

and honor that the Egyptians had for a chariot riders. As in all things, the ancients were sticklers for perfection, and this is what they

did when they drove chariots; they strove to perfect the art of it. On the other hand, charioteering was more a military element than a

recreational sport, just as one will see for the next activity: horseback riding.

Back to top

Equestrian Sport, Horseback Riding

Although the horse was not introduced into Egypt until the New Kingdom, the ancients picked up its usage plenty quick and became masterful

horseman. Originally, donkeys were the main form of transportation of both royals and commonfolk. This animal was a great means of transportation,

especially good for usage in Egypt. A saddle used for this animal now resides in the Berlin Museum and dates to the New Kingdom.

The Egyptians sometimes imported horses from Sangar, but the credit generally goes to the Hyksos for the introducing the horse into

Egypt--perhaps it was this Asiatic peoples that introduced the horse, but more has yet to be uncovered in this matter.

The earliest evidence of their

use, along with the chariot, has been dated to Dynasty XVII. However, the earliest

mention of

the word "horse" (

htor) appears on a personal stela that dates to Dynasty XIII. Other words from Ancient Egypt that

relate to this word are

ssmt and

smsm. Even though horseback riding was a minor recreational activity, to the Egyptians it was not done with quite

as much fervor as other, more documented sports and games. However, this does not mean that the Egyptians were not horseback riders.

Nevertheless, there have been no depictions of Egyptians horseback riding found as of yet, though barbarians were

represented thus and the Semitic goddess of war was also depicted on horseback. Generally, horses attached to a chariot used

for war, campaigning, and hunting are the only evidence of horses.

Evidence of horseback riding by a non-Egyptian can be seen

on a battle ax. Evidence of horseback riding, of only man and horse together with only a saddle between them, comes in the

form of the written word, of literary illusions: the officers were said to have been on horseback, in pursuit of the enemy;

a story tells us of the pharaoh mounting a horse and another ruler was accompanied by his wife who was on horseback; and a

fighter received a letter from an opponent by a messenger who appeared to him on horseback. Evidence of the chariot and horse

are the following: in the tomb of Horemheb, which is located in Luxor and dates to Dynasty 18 circa 1900 B.C.E.; at the Luxor Temple,

which dates to Dynasty 18 circa 1280 B.C.E. and depicts a cavalry; also depicting a cavalry is one that dates to Dynasty 26 circa

700 B.C.E.; and at Medinat Habu, the mortuary temple of Ramesses III, which illustrates equipment for a horse (a saddle

and other accoutrement), which dates to Dynasty 20 circa 1180 B.C.E.

Back to top

Football

The most surprising element of Egyptian sporting may be that the Ancient Egyptians were the first to institute a form of sport known to most Europeans

as "football" and or "soccer" to Americans. As is the case for evidence of handball, evidence of football in Ancient Egypt can be

seem depicted on the walls of Beni Hassan where the girls who are shown playing handball with each other also play football,

kicking a ball with their legs and executing passes with it. What a great reason to give the next World Cup concession to

Egypt, as they were the first nation to invent it.

Back to top

Handball

Some depictions at Beni Hassan in Minya, especially at the tombs of Khiti and Baket, which date to Dynasty XI circa 2,000 B.C.E., offer

us a glimpse at what a handball game might have looked like, who played, how many played, and with what equipment the players

played the game. The most likely way players of handball set themselves up to play the game was to have two or more bend

over, while carrying a person on each of their backs. Once there are two or more people on piggy-back, they would

then toss around and catch a handball or juggle two to three balls at once. There is evidence of this particular game on one

wall painting at Tel-el Amarna, ancient Akhetaten. This painting shows a group of girls--most likely of royal status,

as the headdresses each wears denotes. Not only did girls play this sport but also boys. One theory voices that the beauty

of a girl was measured by the strength of her back--her ability to play this game, to carry another person on her back,

would give credit to her beauty. According to the ancients, women were in charge of bearing heavy burdens such as birthing

children and carrying heavy things--they were thought to be the stronger gender, whereas men were the directors.

Back to top

Hockey

The prime area from where the evidence of this sport can be found in tombs at Beni Hassan. Drawings in Menia Governate illustrate

hockey players, holding bat-like sticks, most likely made from the wood of palm or tamarisk branches or stalks. At the end

of such sticks was a bent edge, which resembles the form of the modern day hockey stick. As for the ball used for the ancient

game: it was made from papyrus fibers, which were compressed within two pieces of leather, shaped in a semicircle. At times,

the ball was tinted to make its color contrasting to the ground on which it was played. Usually it was dyed in two or more

colors.

Back to top

Hunting

Ends To The Means:

Perhaps the most beloved sport in which royalty and peasant alike engaged was hunting both in the marshes and on land

for either sport or for leisure. Peasants hunted mainly on foot in order to provide their families with food, whereas kings,

courtiers, dignitaries, and other folks of royalty hunted in order to display their strength, courage, valor, and mastery

over all animals they hunted. Peasants would not have hunted to prove anything, but being a successful hunter without a doubt

symbolized his strength, courage, valor, and mastery.

In general, hunting had a ritualistic connotation for anyone who engaged in it. No greater civilization

has ever revered more the animals they hunted than the Ancient Egyptians, with the exception of the Native Americans. Like

the latter, the Ancient Egyptians prayed to various gods and goddesses of animal images--say, praying to Bastet or to Mafdet

for success in hunting wild cat or praying to Sobek that they may avoid being eaten by crocodile--ere going out

on the hunt, to ensure their safety and the bounty for which they hoped would come in plenty. Not only did success come in

praying for it, but also it came by knowing their prey well. The Egyptians knew how each species of animal mated, ate, by what means

each normally died, and other personal traits they felt important to know in order to ensure success on the hunt. It usually

worked. What is more, animals such as the lion, represented royalty and there was something more to hunting lion than just

for the fun of it. Being the image of the pharaoh's power and leadership and the dangers that came with hunting such

a beast, the lion embodied the pharaoh's ability to triumph over his enemies and further symbolized the pharaoh's

courage.

Type Of Game On Land:

The Ancient Egyptians hunted both on the waters of the River Nile and in the red sands of the desert. The game after

which they chased on land varied from dynasty to dynasty. For example, during the pre-dynastic period--the time before

the unification of Egypt--agricultural Egypt had not yet been established. The area next to the Nile was more of a jungle complex than

anything else, with its tamarisk trees, thickets, papyrus plants and reeds. This meant that all sorts of large game on four

legs prowled around: elephant, giraffe, lions, rhinoceros and wild boar. Other animals the Egyptians hunted included antelope,

gazelle, stags, ibex, ostrich, fox, hare, hyena, and many species of deer and bird, just to name a handful. Later on, the

first few dynasties hailed the first signs of agricultural development: farmers began to drain the marshes where once large

game lived, extending the agricultural boundaries. All this cause was not without effect: when farmers drained the marshes,

they chased all large game--elephant, giraffe, rhinoceros, and wild board being a few examples--away from the valley.

Despite this change in economics and the loss of larger game, the Old Kingdom Egyptians still hunted for food--they were

actually quite good at hunting at this time. The game they hunted was of the faster sort and included animals they had hunted

before, such as lions, gazelle, stags, and ostrich.

Type Of Game In The Marshes:

Just as the ancients were great hunters on land, they were also just as great in the marshes and waters of the River

Nile. The animals the Egyptians hunted at this time included any of the following: fish, duck, crocodile, or hippopotami.

One artifact that makes known the type of animal hunted in or by water is a fragmented papyrus named The Pleasures of Fishing

and Fowling. Let us first examine fishing.

To us westerners, fishing might be a pastime, a means of nutrition, or both. To the Ancient Egyptian, fishing was both a pastime and

a means of nourishment; the Egyptians always considered these two aspects of fishing one-in-the-same. Examine how you fish, next time you go; how fish

market venders sell their fish; and how they prepare fish to sell. Whatever one observes will be a near replica of how the ancients used to do it

(with far less technological advances as are evident now, of course).

Like most recreational activities in which the ancients engaged, in particular peasants, fishing was depicted on many-a

tomb painting: Egyptian fishers, much like today, could be seen lounging lazily about in chairs alongside the Nile or beside

their garden pools--if they were so lucky to have one--waiting for a single tug. Depictions also have shown us the

playful side of fishing: on another tomb painting, one can see fishermen jostling each others' fishing rods--the

fishing rod, a New Kingdom technique used for so many things. Fishing was also a measure of professionalism.

Professional fishers stood on canoes made of papyrus, wielded harpoons, and waited for the right opportunity to strike

As is no doubt evident, fishing was a great pastime and sport among the Egyptians and having an abundant supply of

species of fish helped in the matter. Among the many fish caught for sport--a count of around 20 different species, as

shown on tomb paintings and reliefs--were the following: Nile perch; eel; catfish; carp; mullet; tilapia or "

bolti"; elephant-snout; tiger fish; the

amphibious

clarias; the electric catfish, called

malapterurus electricus, which packs a powerful 200 volt punch; and moonfish. The Egyptians considered the Nile

as the most sacred and the best of the lot.

Just as there were a great many fish after which both royal and commoner hunted either for sport or for necessity,

there was an equal amount of fowl after which they hunted. These included the ser, which was a rather fat goose; the terp;

the hoopoe; crane; ducks; quail; the much sought-after bird off Arabia, which supposedly smelt of myrrh; and many others.

Whether hunting or sporting in the water, there were dangers all the same, be it from crocodile or other fish-eating

aqua dwellers such as poisonous catfish. Crocodile finding a fish on a line could without effort make a meal out of the fisherman--if

he should fall overboard--on whose line this fish was caught.

It was not only in the mind of a hunter to be wary of the crocodile to keep from being injured by such an animal, but

also to be seen as brave in hunting such a dangerous and sacred beast. In ancient times, it was an honor and a feat of which

to be proud if one successfully hunted the crocodile. However, no depictions of such a sport exist, which gives one reason

to believe that the Egyptians revered the crocodile with such respect that depicting it being hunted was not conducive to their reverence.

One the other hand, the hippopotamus--an even more dangerous creature to hunt because of its size

and powerful jaws that can crush a crocodile--was extensively shown being hunted. It too was dangerous and sacred to

the Egyptians like the crocodile. Successfully hunting a hippopotamus, which took several jabs of the harpoon at times, was

also cause for great pride to whoever hunted it. It must have been the best mode of feeling proud and gaining great recognition

and reverence from one's people, owing to the fact that Old Kingdom depictions of such hunting are plenty.

Preparation Of Food After Hunting:

If a fisherman caught his fish without incident, he prepared to eat it by first cleaning it and then cooking

it by doing any of the following: pickling, roasting, salting, drying in the sun, or boiling. It was also usual for a fisherman

who was part of a group of men working for a master to collect their lot of fish to string the fish through their gills, attach

their catch of fish in rows on a stick, and then carry it all to the fish dealers. Just as a lone fisherman might prepare

fish for his family's next meal, so also did the fish dealers: they sat low to the ground, near a small table, and

cleaned out and cut up the freshly caught fish. Afterward, he hung the fish on strings in order for them to

dry out in the sun. Sometimes, to spare the dealer from this preparation process, to prevent spoiling, and if the fishermen's

trip was a rather long one, the fishermen did the cleaning and cutting on their boats.

Hunting Techniques; Equipment Used:

During the earlier dynasties, hunting on land was done on foot; only until the advent of the usage of the horse and chariot (around

2,000 B.C.E. thanks to the Hyksos) did the king and his colleagues hunt this way. For either means of hunting, the

key technique that the ancients employed to hunt their prey resembled a wild animal's: to lie-in-wait

for animals or to lure a large number of them to a specific locale like a body of water or a valley. Afterward,

the hunters attacked their prey en bloc with throwing sticks, boomerangs, or nets to catch birds; spears or arrows

to catch land or water animals; or specially made nets to capture fish. Sometimes, the ancients used dogs (perhaps

a type of greyhound, so tomb paintings illustrate) or tamed cheetah as accompaniment on the hunt.

When the ancients hunted in the marshes, especially for fish, they used nets, traps, pens, hooks, or harpoons--this

type of equipment was in great employ during the Old and Middle Kingdoms. In its earliest usage, the harpoon was a common

tool to spear fish, usually two at a time: hunters could catch one fish on either end of the double-edged harpoon, which was made

of a thin piece of wood 3 yards long with barbs attached to either end. Later on, however, the spear was used in a more recreational

setting, where fishing for necessity was not the aim; rather, it was used to measure skill and technique. It was also during the Old

Kingdom through the New Kingdom that hunters of hippopotami used harpoons. It was designed so that if one punctured the

skin of this animal the shaft of the weapon would separate from the spear, which was attached to a string, a

hippo fishing pole, if you will. Being such powerful creatures with killer jaws, hunters of this animal dared only to approach it by boat (what

fool would jump in the water with it, aside from the Crocodile Hunter)? The method of killing the animal came in not

one but several jabs of a harpoon, but in several. If it happend that the hippo retreated after the hunter striked it with the harpoon,

the hunter waited for it to return to the surface. Because the harpoon's spear point was detachable from the shaft, it was easy for the

hunter to track the hippo's movements under water no matter how deep it swam--the hunter just let out the harpoon's line.

Having the ability to hold its breath under water for a limited time, the hippo eventually came up for air. At this moment,

the hunter wounded the creature again. When the hippo gave into weakness, the hunter tiee a rope around the animal's head

and then dragged its body to shore.

Other tools the ancients used to fish for either recreation or necessity were bow- and drag-nets. These were the

favorite and more convenient pieces of equipment used mostly by the common fisherman at the start of the Old Kingdom.

These nets are almost similar in design to modern ones, where corks (on top) and weights (on bottom) were

fastened to either end of the net. Once it was situated upright in the water and when a good amount of fish were wading within

the net's boundaries, the fishermen pulled on strings that were attached to either end of the net and trapped a good

thirty heavy fish of various kinds, previously mentioned. When fishermen used hooks, they were simple in structure, made of bone

and attached to a line. A typical bone hook measured anywhere from 8mm to 18mm. By Dynasty XII, the ancients started to

make their hooks from metal in lieu of bone. Some of these hooks could be made with or without barb.

The Ancient Egyptians also enjoyed hunting or sporting for fowl, which included crane, duck, geese, and quail. The

nobility employed throwing sticks to knock their prey out of the sky--it illustrated their skilled aim, not necessarily

their success in hunting for food. The common Egyptian preferred to net fowl like they did fish. Otherwise stated,

Egyptians of royal blood used spears, throw sticks, or harpoons to hunt fish, birds, and hippopotami for recreation,

respectively--this equipment was efficient enough to kill one animal at a time. On the other hand, the commoner used nets or snares for hunting

for the need of food--this equipment was efficient enough to catch a large amount of animal. The way the common Egyptians lured water dwelling creatures

was to bait a trap with corn, maggots, or worms. Contrarily, when royals used spears, throw sticks, or harpoons, it was

not necessary to provide bait. The royal fisherman's skill was the only thing that was required of him during the hunt.

Typically, the royal Egyptian wore his honorable costume when he went out to hunt any animal he pleased and was accompanied

by his wife and his children. This costume was composed of a royal skirt, a beautiful wig, and a false beard. His wife

might wear a sheath dress covered by a beaded collar and a wig of longer length than that of her husband's. The royal

man's children were usually naked and wore a number of bracelets, armlets, or anklets. As mentioned before, if the

royal was hunting birds in the marshes, he would float through the forest of papyrus reeds and fling his boomerang-like

throw stick (typically made from a small piece of hard wood that was bent in a certain way so as to cause it to return to

the thrower after he threw it) at the neck of a bird, which caused its neck to break if the fisherman was so skilled. When the bird fell to the water, his

wife collected it as her husband scoped the air for more targets. The children, on the other hand, would playfully swirled

the water with their fingers as the boat sailed through it.

The commoner, whose aim at hunting was of the necessary sort, did not trouble himself with decorating his body with unnecessary

clothing, such as a skirt, a wig, or a false beard, the last article being one he would never have worn. It was commonplace to start

off with wearing a skirt, but it was not an unusual event to discard this, leaving nothing concealed. This was optimal when hunting became

intense, especially when the bird and fish nets were full to the brim with bird and fish. Rather than be accompanied by wife

and children, the common Egyptian was accompanied by a handful of his best mates. Sometimes, a master had a small group of men who worked

for him in hunting. In either case, this group of hunters would far exceed the royal group, the latter group's only master of hunting being the king.

The costume and number of hunters in a group were not the only aspects that differed between royal recreation

and common persons hunting for food, but also the way the latter group of people caught their birds and fish. As mentioned

before, snares and nets were mostly used and were baited either with maggots or other types of food or with a decoy bird. It

is difficult to be certain of the actual bait used, as most of the scenes depicting such hunting occur at the moment a group

of men catch their lot of prey. However, just from observation, one can determine that bait was used and that the nets and

snars, especially for bird-catching, measured about 10 feet by 12 feet. Much like how modern-day hunters trap their prey,

during the Old Kingdom, the common Egyptian concealed his net or snare beneath the reeds floating on the water. In silence,

the common angler waited until a great many birds sat their fannies on the traps to delight themselves with the bait. Once the number

of birds within the concealed net or snare was to the master's liking, usually around 30 or 40 birds, he waved a

piece of linen in the air to signal to his men to start pulling on the string that was attached to the net or snare in order

to close it. The master would also help in closing the net as well as break some of the wings of the birds inside

to prevent any from escaping. Once caught, the Egyptian fisherman sorted the trapped birds and put them into cages, ready for transport.

Back to top

Marathon Running

In ancient times as well as in modern times, anyone from any social class knows how to and can run. However, in ancient times it was the king for whom

running was of the utmost importance, especially to measure his ability to rule. Typically, the king and those born on the

same day participated in a marathon race of sorts, where each runner fasted until he covered 180 stages of the race. Whether

or not this was part of the following festival, which is of a more sacred significance, is not certain.

Back to top

The heb sed festival:

The

heb sed festival, also known as the "Royal Jubilee Festival," was the most famous and ancient of all running sports in Ancient Egypt.

Unlike other sports, this was a race for only one person: the king. The festival took place after the 30th year of a

pharaoh's reign, thus it is evident that only a handful of Egyptian rulers have ever gone through this ritualistic run.

However, on some reliefs and for some kings, the festival is celebrated earlier. What is more, rulers that had a relatively

shorter reign, say of less than 30 years, would only have been depicted symbolically carrying out this duty of kingship.

The point of the exercise was to renew the ruler's royal powers and position as king. As a means of illustrating

his right to rule, Pharaoh was sometimes depicted running in step with an Apis bull, the living image of Ptah when alive

and of Osiris when dead. When Pharaoh successfully executed the race, re-coronation took place. It was not only in life that

Pharaoh ran the

heb sed and renewed his power and position, but also in death. Evidence of the

heb sed during the

Afterlife can be found depicted on an alabaster vase, which scholars found in a chamber under Djoser's pyramid.

A great example of a

heb sed court--where Pharaoh engaged in this ceremony--can be found at Saqqara, near King Djoser's step pyramid. On the walls

of the Southern Tomb, on the south side of the Great Courtyard, there are depictions of King Djoser running the

heb sed race; here he has renewed his royal position,

rightfully being called

Horus Netjerikhet (meaning "God of the Horizon). At the center of the Great Courtyard resides a set of semi-circular blocks, between which Djoser

ran the

heb sed in the Afterlife. It is said that these semi-circular blocks had some cosmic connotation, representing

the order of the universe. On the other hand, these markers may have represented the frontiers of Egypt, symbolizing the boundaries of Pharaoh's dominion. On the east side

of the Great Courtyard is a temple, named Temple T, perhaps a pavilion through or at which King Djoser ran or waited at a certain point

in the ceremony, respectively. Following the curve of the walls of Temple T, one enters the

heb sed court. It is at the center of this court that steps would have led up to a platform roofed by a canopy; here King Djoser would have

been re-crowned twice: once as the Ruler of Lower Egypt and another time as the Ruler of Upper Egypt.

The earliest evidence of this festival can be found on a small ebony label, which used to be attached to an oil jar

perhaps belonging to King Den of Dynasty I, in whose tomb at Abydos this object was found. On it one can see a tiny figure of a man, running through a court and then being crowned on a canopied

platform. From this date through Pharaonic Egypt, the Egyptian rulers practiced this festival. For example and as mentioned before, there is a wonderful mural at Saqqara, dating to 2,650

B.C.E., which depicts king Djoser participating in his

heb sed festival. The quality

of workmanship accentuates the significance of physical fitness that the ancients held in high opinion. Here, the artist shows his

skill in depicting the leanness of Pharaoh's muscles; the anatomical correctness of arms, legs and torso; and movement

only such a skilled artist could capture. One finds also the remains of the

heb sed

boundaries of Hatshepsut at the Red Chapel at Karnak, which dates to 1,480 B.C.E., where also

she is depicted running with the Apis bull between these boundaries. Inside the Theban mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, one sees the king running

his race, though in a different manner as the previous two. Instead of running his race in a court near his tomb, descriptions

indicate he did so, on the great artificial lake he designed at Malkata. However, Amenhotep III was not the only ruler to

break with tradition: the heretic king, Akhenaten, did so as well--big surprise. Evidence of Akhenaten running his

heb sed race appear in

the colonnade court of the Temple of Aten at Karnak. Traditionally, Pharaoh was the only runner in the

race; however Akhenaten, Nefertiti, their daughters, and the Aten took part in the action together. The most intriguing of the lot

is the aten; never has a god been depicted in a

heb sed festival, other than the

Apis bull. The Aten's appearance and participation in the festival was necessary, as Akhenaten's philosophy implied, because both king and god

were considered one-in-the-same. Pharaohs of Dynasties XIX and XX engage also in their

royal duty to re-coronation. For example, Seti I carried out his

heb sed duty, which is depicted

at Abydos and dates to 1,300 B.C.E. His son, Ramesses II, is depicted running the

heb sed on the inner walls of the hypostyle hall at the Temple of

Karnak, on a dilapidated block found at Tanis, and at Abu Simbel (the latter dating to 1,280 B.C.E.). Ramesses III, a Dynasty XX ruler, participated in his Royal Jubilee Festival, which

is depicted at his mortuary temple at Medinat Habu and dates to 1,880 B.C.E.

Other evidence of this festival taking place span all the way to Dynasty XXII, where Osorkon II is depicted in his

heb sed uniform--usually a short wrapped skirt, a crown, a false beard, a flail, and an object yet to be

identified. This depiction of Osorkon II is located in scenes on the wall of the temple dedicated to Bastet, at Bubastis.

At Kom Ombo, Ptolemy VIII, a foreign king, is depicted on carved reliefs: here he receive gifts from Horus.

Back to top

Tennis, Badminton

Similar to the execution of handball, girls and boys (and even Pharaoh and his wife), played a game that resembles

modern tennis or badminton. Evidence of such matches can be found in paintings at Tel-el Amarna (ancient Akhetaten).

Although it is far from clear, Egypt--along with Greece and Rome--may have been one of the first ancient civilizations to

engage (invent?) the game of tennis. Others accredit the origins of tennis to French monks of Medieval France.

What is in Ancient Egypt's favor is the apparent similarities between Arabic words--dating from ancient times--and

English derivatives: Tinnis or Tanis, the city near the Delta, and

rahat (in English it means

"palm of the hand") correspond to "tennis" and "racquet," respectively.

Back to top

The Performing Arts

Concerts

Musical performances were an additional importance in the worship of deities and rulers at the cults dedicated to either. The common population also enjoyed

such performances. During the Old Kingdom, concerts could be composed of two harpists, one small and one large

flute musician, and one male singer for every instrumentalist who clapped his hands to keep a beat. During all kingdoms, one or more

singers always accompanied flutists, whereas harps could be the only accompaniment to singers. By the New

Kingdom, women singers were more frequent in concerts and often sang with men, all of whom

could appear with a small symphony of the following instruments: a large harp, two lutes or one lute and lyre, and a double

flute.

Usually, such concerts were the main entertainment during feasts composed of family members and friends of royal or high status.

Drinking to the enjoyment of life and becoming inebriated was a frequent happening and was not an inconvenience, but commonplace. [see "happy hour" festivals.]

Back to top

Dancing

From the earliest times in Egypt, we find evidence of dancing; from Pre-Dynastic times, archeologists have found representations of dancing in the form of clay figures that

have their hands raised above their heads as well as depictions on Pre-Dynastic vessels that show women raising their hands

above their heads as others shake rattles or sistra. It is also from tomb and temple scenes from all periods of Dynastic

Egypt that one sees the importance of dancing, acrobatics, gymnastics, and music, of both the religious and secular sort. Most evidence of ancient dancing comes from depictions

inside tombs, which date to the Old and Middle Kingdoms and then disappear completely during the New Kingdom. This does not

mean that New Kingdom Egyptians stopped dancing all together; it might just be that New Kingdom tombs did have dancing scenes

depicted in them. On the other hand, in temples it is the exact opposite: during the New Kingdom, the Late Period,

and onward, one finds dancing scenes. However, in temples dating to the Old and Middle Kingdoms one really does not see anything of

the sort, as Old and Middle Kingdom temples are quite rare. Again, this does not mean that there could not have been dancing

scenes depicted in them. Deterioration or the prospect of finding such evidence could be the case here.

When one thinks of dancing, acrobatics, and gymnastics, one thinks of three different sporting or special events that call

for each to take place. The reason for such a large range of activities being described under one header to examine ancient

dancing, acrobatics, and gymnastics is there was no distinction among the three: the Egyptians believed that dancing,

acrobatics, and gymnastics of any degree were activities cut from the same cloth. Also unlike today, where music can

to provoke dancing, in ancient times, music was really meant to. Instead, it was the clapping of hands

or the playing of percussion instruments like the tambourine, drums, or sistrum that gave dancers the cause to dance. No depictions

or records of stringed or wind instrumentalists have been found to be associated with dancers. If they are depicted together--and

they sometimes were, as where there are instrumentalists, there may also have been dancers close by--there is typically an element

of some sort that separates them. However, this does not negate the fact that dancing and music were not done at the same

time, as one depiction found at Giza and which dates to the New Kingdom shows: here, less than a dozen women wear wigs and diaphanous

gowns, shake tambourines or kettle drums and castanets or sticks, and perhaps twirl about in execution of some sort of

dance, as the flow of some of the female dancers' wigs suggest.

Having been such an important element in religious, ritualistic, and daily life, it may come as a surprise that the ancients did

not have a concrete word that expressed the words "dancing" or "dance." However, from the earliest

records found, the ancients had derivatives, words that are synonyms of this generic word "dance:" the most common

word is

ibw, perhaps meaning "caper" or "frolic;" another common word to describe dance in which an acrobatic might engage was

hbi, or "acrobatic

dance;" a word that described a dance for which performers bore animal-headed clappers was

normal">rwi, which means "to run away;" one word that describes a dance that both non-royal and even animals

executed was called

ksks, meaning "twist;" the word for an Old Kingdom dance performed exclusively by a pair of men was called

trf; and then there is